The Return of the Screwball: A Mr. Funny Bones Gothic Novelty (with AI Boost)

Cover – I – II – III– IV– V– VI bis

VII – VIII – IX –X – XI – XII – XIII

Copyright (c) 2023 MP

Little Hope: A Minor Tragedy: A Mr. Funny Bones Long Short Story

Cover – Chapter 1 – Chapter 2 – Chapter 3 – Chapter 4 – Chapter 5 – Chapter 6 – Chapter 7 – Chapter 8 – Chapter 9

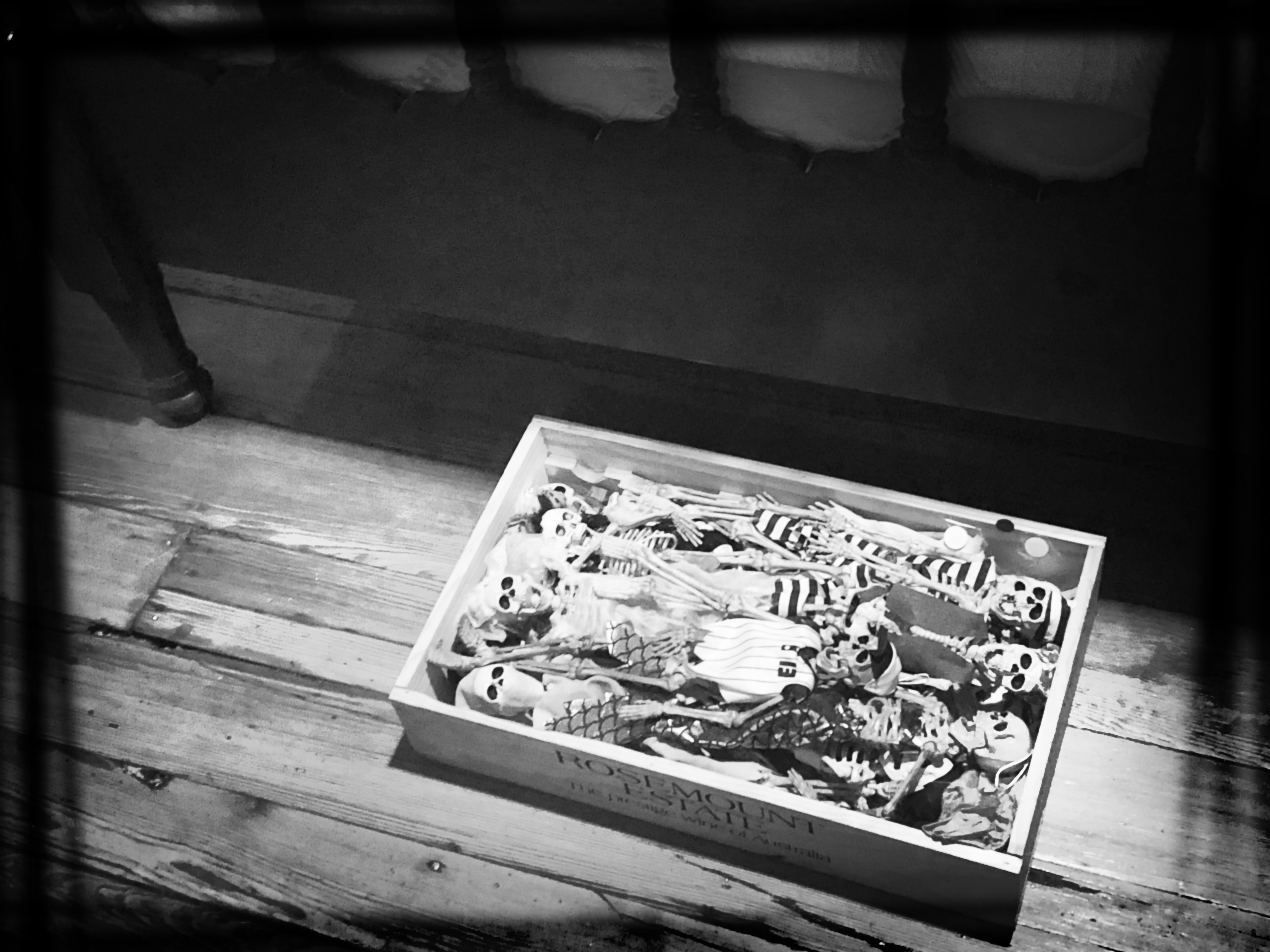

Little Hope never skips breakfast, she thought to herself. Her summonses to the table unanswered, Hope climbed the stairs to check on her daughter. When she opened the door to Little Hope’s bedroom, she averted her eyes as usual from the corner opposite and spied an empty bed. She scanned the room for clues and saw a pile of dismembered toy skeletons on the wooden floor.

Back downstairs, she looked out the kitchen window and noticed the open shed door. She was afraid she might have forgotten to close and lock it after her last drunken cry-mowing session. She dispatched Johnny to check out front and at the cemetery for his sister while she checked the backyard.

From the end of Main Street at the corner of the cemetery, Johnny looked up and down the highway. In the distance to the east, he saw his sister, Little Hope, pedaling furiously into the sun.

The End

“Stop laughing at me!” Little Hope shouted at the two large skeletons propped up in the corner of her bedroom. They didn’t listen, so she sprang from her bed, grabbed the cycling cap off Mr. Funny Bones’s skull and, holding it by the visor, hooked the cap under his jaw and pulled it over his frontal bone, fully covering his face. She repeated the brutal process on Funnier. “That should shut you both up for a while,” she said scornfully.

She never should have gone into the shed. She hadn’t been inside it for months, from the moment her mother put a lock on it, and she wanted to ride her bicycle again. After several unsuccessful attempts, including a couple tantrums, she took advantage of a lapse in protocol–her mother had left the shed unlocked–and went in to get it herself.

To the left of the spot where her mother stored the lawnmower hung Uncle Mack’s road bike. Although covered in dust and its tires deflated, the bike looked just as Little Hope remembered it. Beneath Uncle Mack’s bike, stacked on the wooden floor like a pile of bones, were the barely recognizable mangled wheels and shattered carbon frame of what used to be her father’s.

The last time Little Hope had seen her father and his bicycle, both were intact. Although Little Hope’s mother had explained the accident to her and Johnny in general terms, she had withheld the details and the horrific evidence of it from her children. The sight inside the shed laid bare for Little Hope the violence and inequity of her father’s and Uncle Mack’s final moments.

After that trip to the shed, everything having to do with Uncle Mack degenerated into a source of torment for her. The toy skeletons, the stuffed animals, the pictures of the places he had visited–even the nicknames like Only Street that had become part of her family’s lexicon–fed an incipient rage and enveloping sorrow. She felt as if she were trapped underwater, drowning in her own bedroom. Not even her spirit animal could rescue her.

Lying on her bed exhausted after a turbulent cry, Little Hope stared at the cloud drawing on her ceiling. Her mind drifted to that one evening at Simpson’s Garage when, instead of Herbie Goes Bananas, Jake ended up showing the movie, Poltergeist, because of a mix-up at the video rental store. She distinctly remembered the quirky little woman with the teased hair, Tangina, who had been brought into the house to rid it of its demons.

In the movie, Tangina delivered many memorable lines that Little Hope, Uncle Mack, and her family would repeat jokingly whenever a situation warranted them. Those lines weren’t so funny anymore. She hoped that her father and Uncle Mack had remembered to step into the light and that they had found serenity and peace there.

After nearly six months’ worth of conversations with the Kellers, Selters, Mr. Lewis, and Mrs. Smith in the cemetery, it had finally dawned on her that they weren’t trapped underground. On the contrary, they were free. They had simply transitioned from one state of being to another. The transition might have involved agony. It might have happened quietly. The burden and the pain of adjusting to the holes that had formed in their wake fell to those they had left behind.

For a fleeting moment, she felt ancient for her age, as if taken over by an old soul that had witnessed the passage of a thousand lifetimes. Reflecting with frightful clarity on her short life, she had, in fact, caught glimpses of what that burden looked like in her mother, her grandmother, Jake Simpson, and even in Mr. Smith, for whom the arc of adjustment seemed tragically long. She just hadn’t recognized it at the time for what it truly was. She got up from her bed and went over to her mirror to see if she, too, now bore the signs of that burden in herself.

“‘You’ve got to keep going,’ it says, Momma, ‘despite your desire to call it quits.’” Little Hope stopped reading her mother’s daily horoscope aloud because she didn’t recognize the next word. Having heard enough and taking advantage of the pause in her daughter’s recitation of what she had already read for herself earlier that morning, Hope gently encouraged Little Hope to make the most of the nice weather and go outside and play.

Nearly six months had passed since the accident. Hope had pretty much memorized the state police crash report by heart, having had to paraphrase it countless times for curious relatives and friends. As much as she tried, she couldn’t expel the details from the front of her mind.

The report, based mostly on a description from the one witness at the scene, stated that on Saturday, April 7th, Mack Hardy abruptly let go of his handlebars and lost control of his bicycle near milepost 40 on westbound state highway 206, approximately 100 yards from the intersection with Main Street. To avoid colliding with Mr. Hardy, whom he was accompanying, John Lindberger swerved to his left and hit a pothole, which sent him and his bicycle veering across the center line and into the path of an on-coming utility truck. John Lindberger died at the scene.

The county coroner’s report, which Hope had also memorized, stated that, while riding his bicycle with John Lindberger, Mack Hardy suffered a massive stroke in the vicinity of milepost 40 on westbound state highway 206, possibly caused by a diagnosed but untreated atrial septal defect. He died at the scene.

Hope distinctly remembered that sunless morning. John and Mack had gotten off to a late start because Mack wasn’t feeling well. She’d suggested that they shorten their planned ride or postpone it and work on the house, but Mack was convinced that his lightheadedness was due to his having skipped breakfast and that the banana and the PayDay he had in the back pocket of his jersey would take care of it. “Only if they’re in your stomach,” Hope remembered replying sarcastically.

“A hole in the heart and a hole in the road makes two holes in the ground…” Hope repeated the tragic arithmetic to herself in disbelief. The irony of it all was so great that she feared that if she didn’t laugh it off, it would crush her completely. Her mother, the priest, the grievance counselor, and even the librarian at Little Hope’s school had all tried to reassure her that time heals all wounds, but she kept coming back to two prophetic lines in a letter one of the township supervisors had written back to Little Hope after one of her status updates on the pothole situation on Only Street. “Some holes you just can’t fill. The best you can do is learn to live with them.”

Thrown at a moment’s notice into the unsought role of a single parent, Hope restructured her life with breakneck speed. She cut her hair and changed her wardrobe. She sold the family minivan and bought an Outback. After years as a full-time mom and homemaker, she joined her mother in managing the basket factory. She wanted to put the house up for sale, but both her mother and a real estate agent told her she wouldn’t get what she and John had originally paid for it in its unfinished state.

Out of necessity and desperation for an escape, she took up yard work. She’d sometimes cut the grass two days in a row. Her children and neighbors thought it was odd but didn’t say anything about it. They didn’t hear her angry outbursts or cries of sorrow over the noise of the lawnmower. They didn’t see the tears that streamed down her face, glistening like beads of sweat before commingling at her lips with chardonnay from the water bottle in her hand. She couldn’t recall whether the water bottle in her hand on any given day was her dead husband‘s or her dead friend’s.

When they were dating, she and John used to joke about her flight attendant’s approach to life. “Be sure to adjust your own mask before helping others” was her unofficial mantra. Some—who was she kidding, most—people in her life and in her past had called her out for her self-absorption. She’d insist every time that her self-absorption was the one way she could ensure that she was sufficiently together mentally and emotionally to be of any use to anybody else. She knew John needed that space, too, which was why she never nagged him about his long bike rides.

She was continually amazed by her own transformation after marrying him. She embraced the role of spouse fully and thrived in the structure, clarity, and sense of duty that the mere exchange of vows had introduced into her life. Now, after the accident, she felt like a stranger in her own body and was dumbstruck with fear that she had somehow lost her footing. She couldn’t engage meaningfully with anyone after the accident, not even with her own children. Trapped in a nightmarish hole too vast to measure, she struggled in vain to find a way out.

She felt utterly useless and powerless against the entropy of their lives. Her daughter had taken to measuring and reporting on the number and size of potholes on their street, naively believing that the township would repair them and somehow change the course of events of the last six months. Her sweet elderly neighbor, Mr. Smith, who had been so good to Little Hope, informed her that her daughter had started talking to the dead, to his late wife in particular, which upset him. He’d even spotted her one afternoon lying next to her father’s grave in the cemetery talking to herself while pointing towards the sky.

As for her son, Johnny, nobody was paying any attention to him, not even her. He was on the verge of becoming a young man, but all the adult men in his life, from his grandfather on down, had disappeared in a matter of a few years. Hope thought fleetingly that Jake Simpson might be able to play the role of mentor at least temporarily, but he was in the midst of a struggle of his own. His lifelong partner had died from a painkiller overdose, and Jake had acquired the habit of taking the same pills.

Several weeks after the accident, the executor of Mack’s estate informed Hope that Mack had left everything to his best friend, John, or his survivors, including a collection of toys designated for Little Hope. The bequest infuriated her. Instead of giving them things, she’d ask herself, why didn’t he give them more time?

When she had her heart attack, she told Mack everything, even more than she told her husband and certainly more than she and John told their children. She told him about how damaged and vulnerable she felt each time the alarm on her phone sounded to remind her to take her medications. She also told him about that moment on the table when, in the middle of her emergency angioplasty, she had seen a white light but even months afterward couldn’t say for sure whether it was from a source in the room or from somewhere else.

She fully signed onto the scientific explanation that the white light could have been a hallucination caused by heightened carbon dioxide levels in the bloodstream and activity in the brain as cells began to die. The possibility that the only white light John might have seen before he died might have been the headlights of the truck that hit him haunted her endlessly.

Why didn’t Mack confide in her about the hole in his heart? Why did he hide it from his best friends? Why didn’t he get treatment? Hope struggled to find it in herself to forgive him. She told her mother as much one evening in her kitchen.

And those damned toy skeletons left to Little Hope, what were she and her daughter to make of them? When Hope didn’t resent them, she envied them. Although not genuine, those cold plastic monstrosities in her mind had already experienced happiness and sorrow, joy and pain, and life and death. In their afterlives, they glided slack-jawed and carefree across time and space. Soon after receiving them, Little Hope dressed the two large ones in cycling caps. The allusion was too much for Hope to bear, which is why she couldn’t step foot in her daughter’s room without averting her eyes.

On the same side of Only Street as her grandmother’s house, on the other side of the basket factory closer to the highway and kitty-corner from the cemetery, stood Little Hope’s own house. Like some of the other houses in Greenfield, the Lindberger house was an old farm house separated long ago from the acreage that once extended from behind it. Little Hope’s grandmother would every so often describe its style disparagingly as “weathered Tyvek,” a pointed reference to its unfinished state of renovation. “It’s suspended, not unfinished,” was her parents’ usual reply.

Upon closer inspection of the exterior of the house, someone with an eye for detail would notice that the windows and doors were either filled and freshly repainted or new. Those details were the key to unlocking the mystery of the interior. Beneath the household clutter inside lay a modern kitchen and bathrooms and a mix of handed-down and new Ethan Allen furniture from the store on the square in the nearby town of Waterford, thoughtfully arranged in a maze of rooms painted in soothing colors and set on refinished hardwood floors.

Unlike with most house renovations, Little Hope’s father, with help from Uncle Mack, had been working, sometimes during the evenings but mostly on the weekends, from the inside out. Her father would always insist that the happiness and comfort of his family came first and that, despite the house’s unfinished appearance from Only Street, finishing the interior mattered more. “It’s what’s on the inside that counts, Hope,” he’d say with a smirk to his wife when she’d ask for a timeline. Little Hope’s mother would just roll her eyes.

After months of work on the house, Little Hope’s father and Uncle Mack pulled back, not for lack of interest or money to finish the renovation but because they were spending more of the weekends riding their bicycles. The bike riding had started from an impulse to get some exercise, relieve stress, and to get back in touch with nature. Over time, it evolved into a named household ritual. The “Mack and Cheese” rides, as Uncle Mack liked to call them, became a regular topic of conversation.

The longer the ride, the better the post-ride stories, and the more Little Hope wanted to hear. But before the storytelling would begin, Little Hope would have to live up to her part of the bargain, grab two beers from the refrigerator, and meet her father and Uncle Mack on the tarp-covered porch. Every so often, she would test them by trying to coax the number of deer they had seen out of them before heading to the fridge. “You know the rules, Little Hope,” her father or Uncle Mack would always say, “a beer for a deer.” And every time, she would giggle and run towards the kitchen for the goods.

Little Hope loved hearing about the deer they saw on their rides, what the deer were doing when they saw them, whether they were eating berries or standing in a stream, and if there were any fawns among them. She also liked hearing about other things they had experienced or seen. Depending on the time of year, her father or Uncle Mack would report on the height of the corn on the other side of the Klinghoffer farm, the sizes of the grape clusters at Watson’s vineyard, or the kinds of wildflowers in bloom along the roadside. If they had passed through “Thrill Valley,” as they liked to call it, they’d brag about the maximum speed they had achieved on the descent but always return to how beautiful it was to pass through the dark and winding tunnel of trees onto the sun-filled, open valley floor.

Some of the roads and farms they’d talk about Little Hope knew from direct experience. During their family rides, she, Johnny, and her mother and father would cover some of the same terrain, though they would never venture as far or pedal as fast as her father and Uncle Mack. She wondered if, during the Mack and Cheese rides, her father would talk to the animals like they all did when they rode their bikes together as a family.

When they’d pass a herd of cows in a field, they’d all shout, “Mooo-ve over!” When they’d see a flock of sheep, especially in the spring around Easter time, they’d blurt, “Too baa-d!” When it came to horses, of which there were many in their area, they’d whinny if they passed a team, say “Hi, horse!” if they saw only one, or exclaim, “Look at you on your high horse!” if they happened to pass a neighbor on horseback.

Regardless of whether her father and Uncle Mack spoke to animals or to each other or rode quietly in synchronicity, Little Hope knew that they both got something good out of it and, as her mother often said, everyone in the house benefited as a result, even if it meant going another weekend without exterior siding.

Of the two men, Uncle Mack benefited more from the weekly rides. Unlike Little Hope’s father, Uncle Mack preferred riding with someone rather than riding alone. Her mother would often tease that Uncle Mack basked in his best friend’s shadow. John was stronger and had been riding bicycles for years, and Uncle Mack, who had arrived late to the sport, relished his best friend’s advice and attention. He proudly wore the mantle of “domestique” to John and liked to push him in a final quick sprint on the highway before turning onto Only Street at the end of each ride.

Even by a child’s standards, the village of Greenfield was small, and Little Hope knew every corner of it.

South of the cemetery barely stood Mr. Smith’s barn, a pitiful yet picturesque Dutch gabled remnant of a farm that once extended eastward for several acres from Only Street. The barn’s tar-papered and asphalt-shingled roof slumped a bit towards the middle and reminded Little Hope of old Mr. Smith himself every time she passed it.

Although she had yet to see for herself, she had heard that in the barn sat Mr. Smith’s rotted old Lincoln Town Car, which he had not driven, let alone touched or looked at, since his wife had died over thirty years ago. The word on the school bus was that Mr. Smith had buried his wife’s corpse in the trunk and that on certain Sundays during the year you could hear a mysterious knocking coming from inside the barn. Little Hope figured the source of the noise must be a loose board since she talks to Mrs. Smith weekly in the cemetery.

Little Hope’s grandmother couldn’t confirm that the barn was, in fact, haunted, but she did remember seeing the Smiths together in the car on Sunday mornings on their way to church. Mrs. Smith always sat in the back seat, which Little Hope couldn’t understand because, based on her experience, the passenger seat in front was the next best thing to being behind the wheel.

Although thirty years had passed since the death of his wife, Mr. Smith didn’t seem bitter or reclusive. He just didn’t go into that barn. He walked around it everyday, though, to check on his Buff Orpingtons or to replace the small American flags on the posts of the surrounding chicken-wired wooden rail fence with new ones or holiday decorations depending on the season. Although her schoolmates dismissed Mr. Smith as a crazy and miserable old man, Little Hope felt he had a kind and generous heart, and she never forgot the time when he gently applied mud to a bee sting on her arm. So much better, she thought, than the meat tenderizer her grandmother had tried to force on her another time she had gotten stung.

Down from the haunted car barn stood Jake Simpson’s Garage, one of two businesses in all of Greenfield. After the cemetery, Simpson’s was the only place on Only Street approaching anything close to a landmark, mainly because of the striped and numbered ‘70s Volkswagen Beetle permanently parked out in front between the garage and Jake Simpson’s house next door. The garage was more of a hobby than a business for Jake, considering the very few clients he had and the even fewer passersby on Greenfield’s single, dead-end street, but the cars and pickups parked in front and around the side of the garage gave the place the appearance of a viable operation. Jake made most of his money plowing driveways and side roads in the winter and hauling away junk the rest of the year.

Pretty much everybody in the township called the Beetle the “Love Bug.” Little Hope’s parents’ and grandparents’ generations were old enough to remember the many Walt Disney movies starring the cheerful anthropomorphic car. Her generation, or the kids in the township high school mainly, called it the Love Bug because they used it, or they tried to at least, as an out-of-the-way, after-dark location for making out.

Little Hope had all the Herbie movies memorized. Some time ago, someone in Greenfield had persuaded Jake to transform the side of his garage into an outdoor movie screen during the summers for free viewings of all the films in the series. People came from all over the township to watch, including the area teens, though Little Hope had overheard that most of them used the occasion to figure out how to break into the Beetle.

Anyone who knew Jake would have expected to find a corpse hidden in it. Little Hope had it on good authority from an older schoolmate, however, that the front trunk contained little more than the spare tire and some faded and water-warped copies of dirty magazines.

Across Only Street from Simpson’s Garage and completing Greenfield’s commercial core was the basket factory. Little Hope knew it well because her grandparents had owned and operated it since before she was born. The Lively Basket Company served the local market gardeners and truck and grape farmers equally, with lines of wooden bushel, peck, and harvest baskets, some with wire handles and lids, to suit their clients’ different needs and budgets.

Little Hope’s grandfather was far more conservative than innovative in his approach to basket making, which the company’s radio and TV ads featuring the Andrews Sisters’ version of “A Bushel and a Peck” from the musical, Guys and Dolls, reinforced to a mind-numbing degree. Her grandmother preserved that tradition as a memorial to her husband after he died.

A small operation, the Lively Basket Company employed twenty-five people, most of whom lived in the nearby towns. The company had only a few Greenfield residents on the payroll. As much as she respected her neighbors, as “chief cook and basket weaver,” as Little Hope’s grandmother liked to say, she refused to hire them just because they lived on the same street. She also didn’t want to become too friendly with any of them because chumminess, she’d always say, breeds gossip. Instead, she supported the people of Greenfield in other ways, mainly by sponsoring the Herbie the Love Bug film festival each summer on the side of Simpson’s Garage.

Little Hope’s grandmother lived in the red and white house between the factory and the Klinghoffer farm. Situated on a slight rise from Only Street, the house was hardly a mansion but, due to her grandfather’s industriousness and her grandmother’s insistence, it had an aura of respectability about it, from its neatly organized and manicured lawn to its fresh asphalt-shingled roof. Whenever she went there, which was fairly often, Little Hope felt like a princess because it was, by all accounts, the nicest house in the village.

Inside, Little Hope’s grandmother’s house was everything one would expect based on the outside. It was crisply painted, nicely furnished, and uncluttered. “It looks like nobody lives there,” Little Hope’s mother once said. “It’s so clean! Unlike our house,” Little Hope replied. Although she didn’t have to take off her shoes and could play in the living room so long as she stayed off the furniture, Little Hope would tip-toe around her grandmother’s house and take extra care when touching or moving anything, down to a kitchen chair. That’s how palatial her grandmother’s house seemed to her.

She didn’t have her own room at her grandmother’s, but she and Johnny treated the spare bedroom as their own and took turns sleeping over at the house. The room had two twin beds with multicolored floral chenille bedspreads, separated by a light birch wood nightstand that matched the dresser on the opposite wall. It didn’t have any toys or stuffed animals, and, other than a couple framed photographs of Little Hope’s mother as a teenager and an old-fashioned tinted photograph of some ancient relatives, the lilac-colored walls were free of decorations. Nothing about the room resembled Little Hope’s own bedroom, but its differentness was a large part of its appeal. At the end of nearly every sleepover, Little Hope would tell her grandmother not to change a thing.

“Go jump in a puddle!” Little Hope’s brother, Johnny, snapped over breakfast.

“Which one? Give me a number!” she replied. Johnny knew at that point that he had few comeback options. Checkmate, Little Hope thought to herself.

Except for Johnny, everyone in the house—everyone in Greenfield, for that matter—knew better than to dare Little Hope to puddle-jump. Over the short span of a few weeks, she had identified and numbered every single pothole on Only Street. Not only that, she had measured and plotted them all on a master map that she periodically updated, copied, and sent along with a prioritized maintenance list to the township’s board of supervisors.

Officially, the street in front of her house was Main Street. For as long as she could remember, Little Hope and her family called it Only Street because, as Uncle Mack had pointed out one evening, you can’t have a Main Street if you have only one street and no secondary ones. Driveways didn’t count, even named ones like her grandmother’s, who always listed her address as “corner of Main Street and Lively Drive, Greenfield.”

Only Street extended southward for about a quarter of a mile from state highway 206 to the Klinghoffer farm, where it ceremoniously dead-ended at the Klinghoffers’ stately air dried drive-through wooden corn crib. Except for the stop sign at the intersection with 206, the entire street was traffic sign and signal free, which was just as well since anyone driving along it had to focus their attention on the holes.

Strung along Only Street from the highway to the corn crib like the potholes was the village of Greenfield itself. Technically, Greenfield wasn’t even a village but an unincorporated community, which meant that it lacked the local recognition often necessary to get even simple things like holes filled and roads fixed.

Although tiny and officially unrecognized, Greenfield had staying power. The community had been around for more than two hundred years, and even though it didn’t have a historical society or museum to celebrate its long existence, it had its own cemetery with headstones from as far back as the early 19th century as testaments to its age.

Uncle Mack and Little Hope’s parents often joked that there were more people buried in Greenfield than living in Greenfield, and by its sheer size, the cemetery bore that out. It took up the entire hillside on the northeast corner of Only Street and the highway. It was, in essence, Greenfield’s gateway. Everyone had to pass by it both coming and going because the intersection was the only way into the village and the only way out, even for the Klinghoffers.

Little Hope knew the cemetery like the back of her hand because she had to walk by it twice a day, five days a week, from her house to the school bus stop and back. To prepare her for that frightening trip, Little Hope’s father took her there regularly to look at the clouds. On nice afternoons, they’d lie on the grass between gravestones and call out the different shapes they saw.

Some cloud spotting sessions with her father were more satisfying than others. On wispy cloud days, they’d spot peacock feathers, geese in flight, and an occasional writhing shark similar to the ones filmed from below for nature shows. Little Hope felt that she and her father performed their best on puffy cloud days, which produced their fair share of sheep but inspired both her and her father to new competitive cloud spotting heights.

One particularly productive afternoon, her father spied a hot fudge sundae. Little Hope countered with a vignette of two women getting their hair done. Later in the day, she sketched that one and taped it on the ceiling above her bed.

The trips to the cemetery continued long after Little Hope boarded the school bus for the first time. No longer frightened by the place, she now went there on her own. She even memorized the names of many of the people and families buried there and treated them like neighbors.

Periodically, she’d compliment the Kellers on their wildflowers or remind the Selters of the lawn maintenance responsibilities that came with having a prominently located plot. She’d clean the leaves off Mr. Lewis’s tombstone. On Sundays, she’d engage in small talk with Mrs. Smith.

The idea of taking one or more of the little skeletons with her to the cemetery had crossed her mind more than once, but she always decided against it. She had Bruiser to consider, after all. She also didn’t want to upset the many skeletons, whom she had come to know, who were still trapped underground.

Sitting on her bed with her back against the headboard, Little Hope had a commanding view of her room. The two large skeletons, Funny and Funnier, occupied the corner opposite and to her right. From there they’d sometimes stare her down and other times watch over her depending on her mood. The wooden box of small skeletons sat at the foot of her bed. She couldn’t see the box from her perch, but she could easily reach down between the rails of the footboard to grab a few for an emergency convening if necessary.

Her bedroom walls were covered with pictures, posters, and other things she’d made or collected over time.

She had two large expanses of wall as her canvases. She dedicated one to herself and another to the world. On the wall of the world Little Hope had created a sprawling collage of pictures she’d carefully extracted from the nature and travel magazines her grandmother handed down to her at the end of every month. Most were of exotic places she wanted to visit one day.

The collage included, for example, pictures of landscapes, elephants, and temples in Sri Lanka, including that country’s peculiar Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. The idea of a single temple dedicated to a single tooth fascinated Little Hope, and the fact that the temple was the centerpiece of a royal palace in the center of a city called Kandy emboldened her to push back against her mother’s dubious assertion that a diet consisting almost exclusively of candy was somehow bad for her teeth.

The East African country of Tanzania, both the mainland Tanganyika and the Zanzibar archipelago, also figured prominently. Her mother had read to her once from a travel magazine that the writer of one of her favorite books, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, took his inspiration for the mysterious candy-making complex from a massive cement factory in the capital city of Dar es Salaam. She was particularly interested in seeing for herself some day the prototype for the extraction pipe that sucked the German boy, Augustus Gloop, out of the chocolate river and off to the boiler room to be turned into fudge. Maybe because she, like Augustus, was a bit pudgy, that scene from the Willy Wonka movie stuck in her mind.

Seated on a chair beneath the collage was a stuffed patchwork elephant that Uncle Mack had brought back from Tanzania. Like the skeletons in the corner and in the box, the elephant came to her prenamed. Uncle Mack had dubbed it Rufiji, after the river in the country. Also on the chair next to Rufiji was another prenamed elephant, Ping Pong, a gift from Cambodia. And next to Ping Pong was Deepdish, a brightly colored patterned elephant with big tusks that Uncle Mack had escorted in his carry-on bag from India.

In the center of the wall dedicated to herself were the campaign signs she’d made for a career day presentation at school. At the time of the assignment, she’d thought she might like to run for public office one day as a district judge or a state senator or a county executive. Unable to settle on a single office, she had made several different signs and waited until just before her presentation to decide which one to show. Her teacher guffawed when she held up the poster with the words, LITTLE HOPE FOR PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES, said that Little Hope was too wise for her age, and gave her an A plus on the spot. Although Little Hope appreciated the high grade, she wasn’t sure she deserved it because she felt she had done a better job on the freehand stars on the campaign sign she had made for her run for Congress.

Alone on a small patch of wall between her bedroom and closet doors hung a picture of a baby hippopotamus that Mr. Chris, the school librarian, had downloaded and printed out for her. In the border across the top he had written in black marker, “Little Hippo, Big Dreams!” The little hippo’s big ears, even bigger eyes, and oversized head were out of proportion to the rest of its body, and its short and sturdy front legs appeared to extend downward from its neck. The one word that kept popping into Little Hope’s head each time she looked at it, which was everyday, was “determined.” She adopted the hippo as her spirit animal.

Every so often, before getting out of bed, Little Hope would lie awake and think about skeletons and hippos. Neither looked very threatening, which was one thing they had in common. The hippo on the wall had a closed, wide grin and big round eyes. The skeletons had big round eye sockets and, because of overuse or shoddy assembly, lower jaws that wouldn’t stay shut, which gave them their perpetual and sometimes annoying gawks.

Every so often, before getting out of bed, Little Hope would lie awake and think about skeletons and hippos. Neither looked very threatening, which was one thing they had in common. The hippo on the wall had a closed, wide grin and big round eyes. The skeletons had big round eye sockets and, because of overuse or shoddy assembly, lower jaws that wouldn’t stay shut, which gave them their perpetual and sometimes annoying gawks.

Another thing they had in common was that neither of them floats. Denser than water, skeletons sink because they can’t displace enough water to stay above the surface. The same with hippos. Although they spend most of their time underwater, they can’t swim. Instead, they seemingly effortlessly glide across river beds and lake bottoms. Their eyes, nostrils, and ears are high enough on their heads that they can remain submerged for hours at a time.

Somewhere beneath the hippo’s bulky body was a skeleton, but Little Hope had a hard time imagining it because the beast’s pink underbelly, large muzzle, and other oversized parts masked the joints and distorted the size and proportion of their bones. In that one important respect, skeletons and hippos were exact opposites. Whereas one was transparent, the other was opaque. The one thing that skeletons had over hippos was intelligibility. Little Hope could understand them easier. They weren’t full of surprises.

Little Hope broke up the symposium and returned the toy skeletons to the lidless wooden box in her bedroom. She had fourteen in all, including two big ones and a rat, and most of them had names. Among the little ones were Nurse Janet, Brad the Surgeon, and their daughter, Missy; Police officer Birdygo, Butterscotch Chip, Amazing Grace, and one elaborately dressed skeleton with unbendable elbows and knees named Chica. The big ones propped up in a corner of the room were Mr. Funny Bones and his twin, Funnier. She used the two of them as hat stands. The rat skeleton with googly eyes perched on the dresser was Butterscotch Chip’s sidekick, Dale.

Little Hope couldn’t take credit for any of the skeletons or any of their names. They’d all come to her prenamed from her dad’s best friend and former Best Man, whom she had always known as Uncle Mack.

She loved hearing Uncle Mack retell the story about how he amassed his—to use her grandmother’s word—morbid collection of skeletons of different sizes in different costumes. It all started, he’d explain, at a local drugstore around Halloween, where he’d spied from the corner of his eye a full-sized, slack-jawed skeleton crouched on a bottom shelf with a tragicomical “Half Price” sticker on his frontal bone. The name, Mr. Funny Bones, came to mind instantly. “And just like that,” he’d say as he snapped his fingers, the idea of acquiring and naming skeletons was born.

Uncle Mack never could pinpoint what had inspired him to start posting photos of Mr. Funny Bones saying silly things or making puns about death on social media, but the response from some of his friends encouraged him to continue. One of his biggest fans was Little Hope’s mother, who saw something eerie yet appealing in his posts. She responded approvingly to every one of them with strings of emojis and likes to coax him into posting more.

Over time, one skeleton led to another. Some he’d picked up from the same drugstore. Others came from farther away. He eventually moved on from one-off posts to stories, some involving costume and scene changes, household props, and complex plot lines. Uncle Mack would always tell Little Hope and her parents that by expanding his collection he was able to keep his stories fresh. And every time, her father and mother would try to get him to admit that he was lonely. If that were truly the case, Little Hope thought to herself, then why doesn’t he just get a girlfriend or a pet?

For someone of Little Hope’s disposition, Uncle Mack’s toy skeletons were the perfect charge. They didn’t require any food or water and didn’t need to be walked or let outside to go to the bathroom. Apart from the one named Butterscotch, whose left leg was flimsily attached to his pelvis with an upholstery tack because of some earlier injury, they didn’t need regular maintenance.

Although Little Hope felt confident in her ability to care for Uncle Mack’s morbid collection, she felt less sure about animating them. Uncle Mack had a knack for dreaming up clever captions and outlandish scenarios that seemed to reach beyond the creative limits of someone her age and experience. Unwilling to go out on a limb with her own skeleton puns and dramas and expose herself to ridicule, she opted instead to create symposiums and other opportunities away from the camera for the skeletons to communicate freely and independently among themselves.

The size and scope of the symposiums varied widely. Sometimes Little Hope would assemble small groups of little skeletons to discuss the major issues of the day, such as climate change and immigration. Other times, she’d pick a topic of local interest, such as the inclusion of bicycle lanes in state-funded highway projects. Every so often, the symposium participants would offer critiques and render judgments. Her mother’s wardrobe was a recurring subject. Once, she convened a group of the smartest skeletons to complete a crossword puzzle her mother had left unfinished. They didn’t get very far, not because they didn’t know the answers, but because they couldn’t hold the pen in their little boney hands.

Whereas Uncle Mack had occasionally taken the skeletons outside for a photo shoot at a bus stop or in a canoe, Little Hope kept them indoors. She did so, she’d tell them, to keep them out of the crosshairs of Bruiser, the neighbor’s unfriendly and unpredictable dog.

The big ones, Funny and Funnier, never left her room. One evening shortly after their arrival, she had overheard her mother tell her grandmother that she wasn’t sure she could ever forgive Uncle Mack. Little Hope figured she could get away with setting up the little ones in the corner of the family room or the kitchen every now and then without feeding her mother’s anger towards him, but Funny and Funnier, and even Dale the rat, were simply too large to escape her mother’s view.