“Fish gotta swim, ladies!”

“Girl gotta fly!”

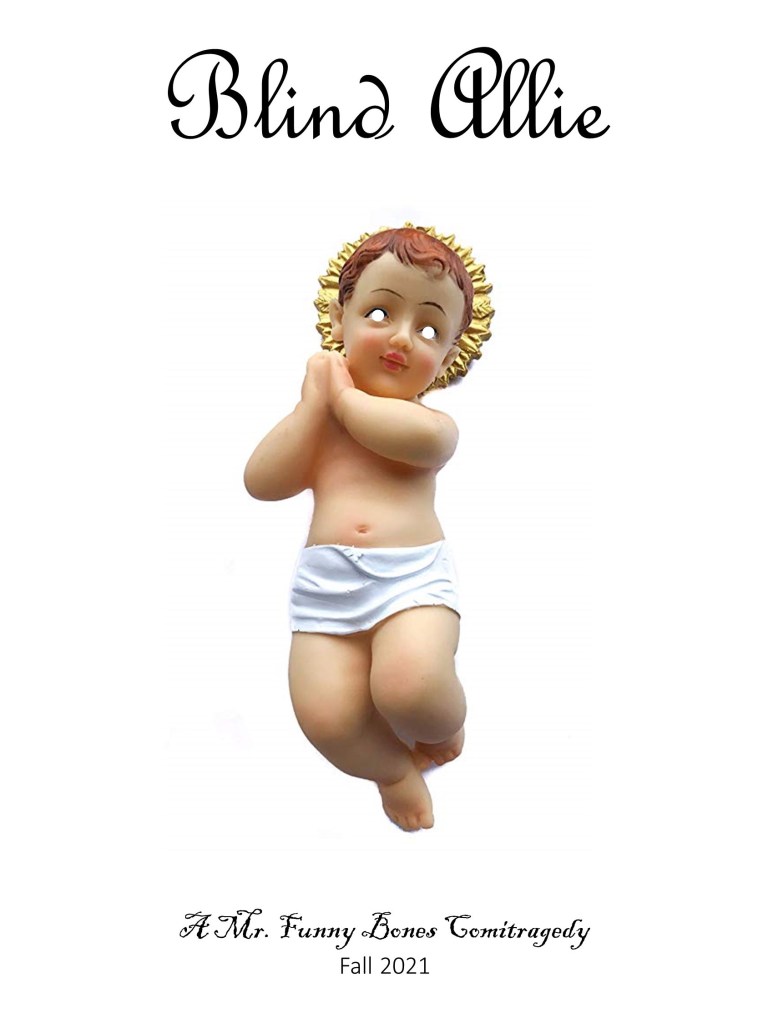

Allie and her teammates performed the call-and-response ritual each time she mounted the block before a practice or real race. They had learned the hard way to leave a good amount of time between their exchange of lines and the starter’s signal. Though a tough pill to swallow for the first several days following that disastrous meet, especially for girls without entrails, their disqualification from that relay medley—their best event as a team—helped solidify their bond and gave birth to the sassy “It was just a twitch!” comeback which they deployed even when it didn’t make sense.

Allie could remember exactly when she seized control of the fish line, which now she and her classmates recognized and respected as her signature phrase. She had every intention of tying the line to her senior picture in the yearbook, and everyone at school expected as much from her. She earned it.

It wasn’t always that way, as the book reminded her. The line and her seizure of it followed a raw emotional path bounded on one end by pride and by triumph on the other with some very dark laps in between.

Lap 1: Playing the role of Julie Dozier in the school’s production of Show Boat was a major accomplishment for her and quite possibly a defining moment in her high school career. Sure, she won every swim race she entered. She excelled in the butterfly. No one even came close to matching her dolphin kick. But being on a stage in front of so many people and both playing a role and singing a song so laden with controversy gave her the existential jolt she never thought she’d receive or need as a dead teen.

Lap 2: The overwhelmingly negative response to her performance on opening night infuriated her. Not the most graceful out of water, she had reluctantly signed onto her drama teacher’s idea that she play the role of Julie in a clawfoot tub. With the help of some of the students from shop class, the production team mounted the tub on wheels so that she could be rolled around on stage during her scenes. No one commented on the delivery of her lines, the authenticity of her makeup and costume, or the quality of her voice. All they talked about instead was how foolish she looked sitting in that tub with her fishtail flapping to the rhythm of the music while singing that line.

Lap 3: Anger soon gave way to shame. For days, Allie beat herself up for blindly signing onto her teacher’s boneheaded idea. She had been so excited about playing her first, and possibly her only, theatrical role that she sacrificed her dignity in exchange for a shot at momentary and, ultimately, illusory fame. She also didn’t think she had a choice. She felt complicit in plotting her own humiliation.

Lap 4: As hoots of “fish gotta swim!” began filling the halls between classes, shame gave way to sadness. She was, after all, a mermaid skeleton. She couldn’t deny it, She was different from her teammates, her classmates, and even her family. Her faith alone sustained her. Faith reminded her she wasn’t alone even though she felt lonely in her scales.

Lap 5: One morning, she awoke and sat up straight in bed. “Fuck it,” she said to no one but herself. If she couldn’t stop the insult, she could at least try to claim it, take it from the people who were hurting her with it and transform it into something others might learn to respect, which she did.

After the fifth lap, Allie decided she’d had enough and got out of the pool.