“‘You’ve got to keep going,’ it says, Momma, ‘despite your desire to call it quits.’” Little Hope stopped reading her mother’s daily horoscope aloud because she didn’t recognize the next word. Having heard enough and taking advantage of the pause in her daughter’s recitation of what she had already read for herself earlier that morning, Hope gently encouraged Little Hope to make the most of the nice weather and go outside and play.

Nearly six months had passed since the accident. Hope had pretty much memorized the state police crash report by heart, having had to paraphrase it countless times for curious relatives and friends. As much as she tried, she couldn’t expel the details from the front of her mind.

The report, based mostly on a description from the one witness at the scene, stated that on Saturday, April 7th, Mack Hardy abruptly let go of his handlebars and lost control of his bicycle near milepost 40 on westbound state highway 206, approximately 100 yards from the intersection with Main Street. To avoid colliding with Mr. Hardy, whom he was accompanying, John Lindberger swerved to his left and hit a pothole, which sent him and his bicycle veering across the center line and into the path of an on-coming utility truck. John Lindberger died at the scene.

The county coroner’s report, which Hope had also memorized, stated that, while riding his bicycle with John Lindberger, Mack Hardy suffered a massive stroke in the vicinity of milepost 40 on westbound state highway 206, possibly caused by a diagnosed but untreated atrial septal defect. He died at the scene.

Hope distinctly remembered that sunless morning. John and Mack had gotten off to a late start because Mack wasn’t feeling well. She’d suggested that they shorten their planned ride or postpone it and work on the house, but Mack was convinced that his lightheadedness was due to his having skipped breakfast and that the banana and the PayDay he had in the back pocket of his jersey would take care of it. “Only if they’re in your stomach,” Hope remembered replying sarcastically.

“A hole in the heart and a hole in the road makes two holes in the ground…” Hope repeated the tragic arithmetic to herself in disbelief. The irony of it all was so great that she feared that if she didn’t laugh it off, it would crush her completely. Her mother, the priest, the grievance counselor, and even the librarian at Little Hope’s school had all tried to reassure her that time heals all wounds, but she kept coming back to two prophetic lines in a letter one of the township supervisors had written back to Little Hope after one of her status updates on the pothole situation on Only Street. “Some holes you just can’t fill. The best you can do is learn to live with them.”

Thrown at a moment’s notice into the unsought role of a single parent, Hope restructured her life with breakneck speed. She cut her hair and changed her wardrobe. She sold the family minivan and bought an Outback. After years as a full-time mom and homemaker, she joined her mother in managing the basket factory. She wanted to put the house up for sale, but both her mother and a real estate agent told her she wouldn’t get what she and John had originally paid for it in its unfinished state.

Out of necessity and desperation for an escape, she took up yard work. She’d sometimes cut the grass two days in a row. Her children and neighbors thought it was odd but didn’t say anything about it. They didn’t hear her angry outbursts or cries of sorrow over the noise of the lawnmower. They didn’t see the tears that streamed down her face, glistening like beads of sweat before commingling at her lips with chardonnay from the water bottle in her hand. She couldn’t recall whether the water bottle in her hand on any given day was her dead husband‘s or her dead friend’s.

When they were dating, she and John used to joke about her flight attendant’s approach to life. “Be sure to adjust your own mask before helping others” was her unofficial mantra. Some—who was she kidding, most—people in her life and in her past had called her out for her self-absorption. She’d insist every time that her self-absorption was the one way she could ensure that she was sufficiently together mentally and emotionally to be of any use to anybody else. She knew John needed that space, too, which was why she never nagged him about his long bike rides.

She was continually amazed by her own transformation after marrying him. She embraced the role of spouse fully and thrived in the structure, clarity, and sense of duty that the mere exchange of vows had introduced into her life. Now, after the accident, she felt like a stranger in her own body and was dumbstruck with fear that she had somehow lost her footing. She couldn’t engage meaningfully with anyone after the accident, not even with her own children. Trapped in a nightmarish hole too vast to measure, she struggled in vain to find a way out.

She felt utterly useless and powerless against the entropy of their lives. Her daughter had taken to measuring and reporting on the number and size of potholes on their street, naively believing that the township would repair them and somehow change the course of events of the last six months. Her sweet elderly neighbor, Mr. Smith, who had been so good to Little Hope, informed her that her daughter had started talking to the dead, to his late wife in particular, which upset him. He’d even spotted her one afternoon lying next to her father’s grave in the cemetery talking to herself while pointing towards the sky.

As for her son, Johnny, nobody was paying any attention to him, not even her. He was on the verge of becoming a young man, but all the adult men in his life, from his grandfather on down, had disappeared in a matter of a few years. Hope thought fleetingly that Jake Simpson might be able to play the role of mentor at least temporarily, but he was in the midst of a struggle of his own. His lifelong partner had died from a painkiller overdose, and Jake had acquired the habit of taking the same pills.

Several weeks after the accident, the executor of Mack’s estate informed Hope that Mack had left everything to his best friend, John, or his survivors, including a collection of toys designated for Little Hope. The bequest infuriated her. Instead of giving them things, she’d ask herself, why didn’t he give them more time?

When she had her heart attack, she told Mack everything, even more than she told her husband and certainly more than she and John told their children. She told him about how damaged and vulnerable she felt each time the alarm on her phone sounded to remind her to take her medications. She also told him about that moment on the table when, in the middle of her emergency angioplasty, she had seen a white light but even months afterward couldn’t say for sure whether it was from a source in the room or from somewhere else.

She fully signed onto the scientific explanation that the white light could have been a hallucination caused by heightened carbon dioxide levels in the bloodstream and activity in the brain as cells began to die. The possibility that the only white light John might have seen before he died might have been the headlights of the truck that hit him haunted her endlessly.

Why didn’t Mack confide in her about the hole in his heart? Why did he hide it from his best friends? Why didn’t he get treatment? Hope struggled to find it in herself to forgive him. She told her mother as much one evening in her kitchen.

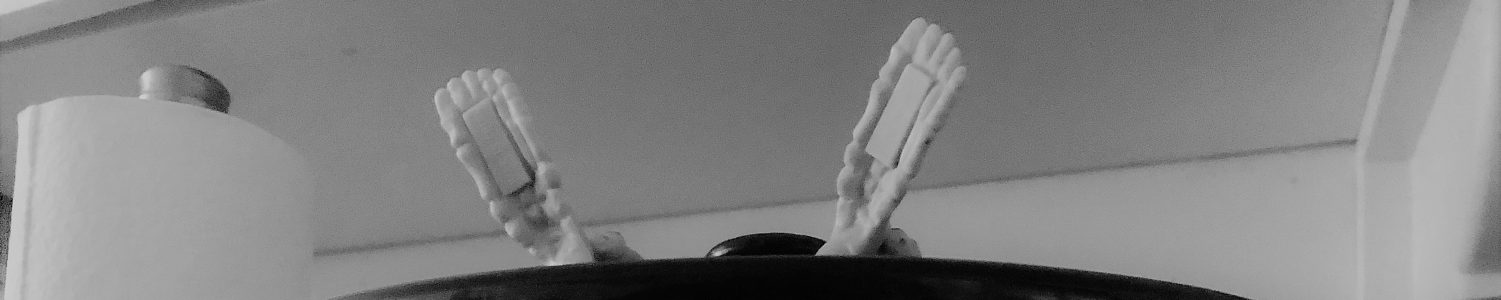

And those damned toy skeletons left to Little Hope, what were she and her daughter to make of them? When Hope didn’t resent them, she envied them. Although not genuine, those cold plastic monstrosities in her mind had already experienced happiness and sorrow, joy and pain, and life and death. In their afterlives, they glided slack-jawed and carefree across time and space. Soon after receiving them, Little Hope dressed the two large ones in cycling caps. The allusion was too much for Hope to bear, which is why she couldn’t step foot in her daughter’s room without averting her eyes.

One thought on “Little Hope, Chapter 7”